Shavuot occurs on the sixth day of the Hebrew month of Sivan. It marks the conclusion of the Counting of the Omer and is understood to be the day that the Torah was given at Mount Sinai. The date of Shavuot is not explicitly mentioned in the Torah. Rather, its occurrence is directly linked to the date of Passover and occurs after the seven-week Counting of the Omer. This counting beginning on the second day of Passover (based on the understanding that “the day after the Shabbat” refers to the festival day of Passover, unlike the theories of the Sadducees and later of the Karaites) and culminating on the 50th day, Shavuot.

In the Torah, it is called Feast of Weeks (Hag ha-Shavuot, Sh’mot/Exodus 34:22); and the Festival of Reaping (Hag ha-Katsir, Sh’mot/Exodus23:16), and Day of the First Fruits (Yom ha-Bikkurim, BaMidbar/Numbers 28:26). The Mishnah and Talmud refer to Shavuot as Atzeret (a solemn closing assembly), as it provides closure for the process of redemption begun at Passover.

Though not clearly described in the Torah as the day of the receiving of the Torah, it is clearly that. We read the following in the book of Sh’mot/Exodus 19:1: “In the third month after the children of Israel were gone forth out of the land of Egypt, that same day (bayom hazeh) came they into the wilderness of Sinai.”

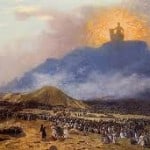

They arrive on “that same day,” the first day of the month of Sivan, the third month. Moshe’s ascent of the mountain followed by the period of preparation amounted to five days, and the revelation, as a result, occurred on the sixth day. This day corresponds exactly to the fiftieth day after Passover, physical liberation followed by spiritual liberation. The reason that the specific event is not described by date in the Bible is, according to the sages, to teach the message the Torah continues to be “received” every day of our lives and not on any specific date.

Yet, around the Shabbat table, my son Yitzchak pointed out that the Torah was, in fact, not actually given to the Israelites on that day. After the awesome revelation of the Ten Statements, Moshe went up for forty days and descended on the 17th day of Tamuz with the Torah. He broke the tablets upon seeing the fall of the Jewish people. After forty days, he went up again for another forty-day period, finally descending on Yom Kippur, the day of Atonement.

This fact implies that the festival of Shavout represents not the giving of the Torah, but rather the Jewish people’s resolve to stand at the foot of the mountain to receive the Torah. That decision to stand and enter into a covenant of obedience to G-d’s direction marks the power of that day. Shavuot represents the wedding of the Jewish people to their Creator. G-d is seen as the groom beckoning His bride, the people of Israel, to stand under His cloud-huppah covering and to accept His marriage contract (ketubah), His Torah. The joy of this festival is that this people agreed to enter the huppah.

A people who had suffered as a slave people for hundreds of years were embarking on a new voyage. They were standing on this Shavuot at the foot of the mountain, ready to accept this new direction: “And all the people answered together, and said: ‘All that HaShem hath spoken we will do.'(Sh’mot/Exodus 19:8)”

This voyage would take them into glorious days, but also through stormy oceans and into many barren and threatening places of wilderness. Many would lose faith on this voyage and others would lose their lives for the sake of the voyage, but the voyage would continue until safe harbor would be reached. This voyage was not begun only for their sakes, but rather it was being undertaken for the whole world. The nations would watch, make incorrect assumptions and then have to re-evaluate and, by so doing, come to a deeper understanding of the hidden spiritual reality that waited to be revealed.

The Torah was not given to a perfect people and neither was it designed to make them a perfect people. The Torah was designed to make them a holy people and, by so doing, to be a vehicle for revealing G-d’s name. the Torah would make them into the very language of G-d. It was given to a people who would find direction, purpose and comfort in the words that would guide their voyage.

They would wander through wilderness after wilderness; yet, it is these words of Torah that would guide them with the understanding that they were a people covenanted with destiny. The prophet Hoshea describes a battered and confused people seeking solace with other suitors following the waves of hatred and persecution. Yet, G-d never loses faith in His people, in spite of the fact that many of them may have lost faith in Him. The prophet describes how G-d entices His people into the wilderness in order to rekindle their relationship: ;

“Therefore, behold, I will allure her, and bring her into the wilderness, and speak tenderly unto her. And I will give her her vineyards from thence, and the valley of Achor for a door of hope; and she shall respond there, as in the days of her youth, and as in the day when she came up out of the land of Egypt…. And I will betroth thee unto Me for ever; yea, I will betroth thee unto Me in righteousness, and in justice, and in lovingkindness, and in compassion. And I will betroth thee unto Me in faithfulness; and thou shalt know HaShem.” (Hoshea 2;18-22)

The book of Numbers is called the book of “In the Wilderness” (BaMidbar), and it is in that wilderness that the Israelites coming out of slavery gained the courage to stand at the foot of Mount Sinai. It is in the midst of the wilderness that they declare their readiness to embark on their new voyage.

As a people, we have experienced many wildernesses and are in the midst of one at this point in our long history. On this Shavuot, we stand again throughout the long night and declare that we are ready again to receive the Torah and to continue the eternal voyage with no fear. After all, we are an eternal people, gifted with the eternal Torah.