The Book of Ruth teaches us man’s enormous potential for greatness – and the catastrophic results if such greatness is misdirected.

On Shavuot we commemorate the Revelation at Sinai – when God descended upon Mount Sinai and proclaimed before the nation “I am the Lord your God.” In the synagogue we read the Book of Ruth that recounts the heartwarming story of Ruth the Moabite, who leaves everything behind to follow her mother-in-law Naomi to the Holy Land, ultimately fully embracing Judaism and becoming great-grandmother to King David.

The relevance of the Book of Ruth to Shavuot is clear enough. Just as we willingly accepted the Torah and the Jewish mission at Sinai, so too did Ruth voluntarily enter the covenant to become a part of that same glorious mission.

But there is a fascinating subplot appearing in the story, one which had far-reaching implications in later Jewish history.

The Book of Ruth begins with a tale of famine in the Holy Land. Elimelech of Bethlehem departs the country for Moab, taking his wife Naomi and their two sons along. He dies in Moab. His wife and sons stay on, and the sons marry non-Jewish women – Moabite princesses by the names of Ruth and Orpah. The sons too perish, and at last Naomi resolves to return to Israel, widowed, childless and impoverished.

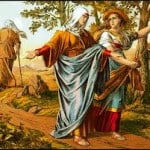

Naomi’s daughters-in-law, Ruth and Orpah, accompany her along the road. As is clear from the Talmud (Yevamot 47b), they were not doing so as a mere courtesy. They too wanted to enter and reside in the Land of Israel. Over their years of marriage, they had become attached to Judaism. They wanted to become full-fledged Jewesses, observing the faith and living in the Land. Naomi attempts to dissuade them three times (vv. 1:8, 1:11 and 1:12; the Talmud derives from her the number of times a potential convert is to be dissuaded). Two times they hold firm; on the third Orpah weakens and returns. Ruth, however, remains strong. She continues with her mother-in-law along the way to the Holy Land.

Naturally, the Book of Ruth continues with the story of Naomi and Ruth – how they return impoverished to Bethlehem, how Ruth attracts the notice of Naomi’s illustrious relative Boaz, and how she unconventionally hints to him that he marry her and preserve Elimelech’s family line.

Orpah, by contrast, disappears from the story and is forgotten. After a brief appearance, she exits the stage of history, presumably no longer playing a role. She was one of so many “almosts” throughout history – people who strove for greatness and immortality but who failed to hang on, instead fading into anonymity.

But our Sages tell us about a fascinating postscript to the story of Orpah. Her descendants would play a major role in Jewish history – on the other side of the fence.

Now we would think that Orpah was not that bad a character. She was a serious candidate for conversion. She took religion and spirituality quite seriously. She just fell slightly short of an all-out conversion.

But the Talmud tells us otherwise. As soon as Orpah parted company with Naomi and Ruth, she went to the absolute opposite extreme. Naomi refers to her as having returned to “her people and her gods” (1:15). The Talmud (Sotah 42b) explains what happened next. Upon leaving Naomi, Orpah ran into a battalion of 100 soldiers. She willingly submitted herself to them all. From the lot of them she became pregnant and bore the giant Goliath, whom the young David would later meet in battle.

How did a woman with such potential greatness go to such wild extremes?

But there is a powerful message in this. Orpah had the potential for greatness. She almost gave up her entire past and homeland to embrace a new religion. She was willing to give her all for her beliefs, to follow Naomi no matter what the cost. She clearly had the seeds of greatness within her.

But she didn’t do it. She backed down. And she took that same zeal and self-sacrifice and brought them to the other side.

What happened to Orpah is what we find happening to many great people throughout history. If a person has the potential for greatness (as we all do) and misuses it, he can take those same enormous energies and use them for the bad. Orpah almost became great. But she couldn’t hold on. And frustrated with religion, she took her same powerful drives for achievement and directed them on the physical plane. Instead of becoming a spiritual giant, she became a mother of physical giants. II Samuel 21 describes how she eventually bore four giants – all of whom were slain by King David and his men.

Orpah’s arch nemesis was Ruth – the one who did hold on, and who turned her commitment to achieve into a lifetime of greatness. Ruth became a mother in Israel, great-grandmother to the spiritual giant David. And Goliath fell to David in battle – in what was in essence a battle between two worldviews – physical versus spiritual. As the Talmud (Sotah 42b) puts it, “The Holy One blessed be He said, ‘Let the sons of the kissed one (of Orpah, whom Naomi kissed goodbye) fall in the hands of the sons of the one who cleaved.’”

The story of Ruth and Orpah is thus a tale of mankind’s enormous potential for accomplishment – and the incredibly high stakes involved depending how he uses that potential.

This also teaches us an important lesson about the Revelation at Sinai, which we celebrate on Shavuot. Human beings have an enormous potential for greatness. We have a natural drive to make something of ourselves, to achieve immortality. God gave Israel the Torah to enable us to direct those drives. The commandments of the Torah are not simply acts to perform, ways of earning heavenly reward. They are a means of developing ourselves, of directing our drive to achieve towards spirituality and perfecting the world.

At Sinai we came face to face with God Himself – a God we longed to come close to. And we were instructed eternally after with the mission of striving towards Him – of bridging the gap between the physical world and the Divine. The Sinaitic encounter awakened within us an enormous drive for spirituality and immortality. Ever since, Jews would not be able to sit still. We would be driven to achieve, to fulfill ourselves, and to become godlike and eternal.

And with such lofty goals set before us, the stakes of life became very high. God gave us the Torah to direct our energies towards goodness and meaningful achievement. We are to take our strongest feelings and emotions and direct them towards God. If we would properly do so, there would be no limit to what we could achieve – and to how meaningful our relationship with God would become. But if not, we would be driven towards every other cause imaginable – Communism, anarchism, liberalism, capitalism, you-name-it-ism. Having seen God at Mount Sinai, we could never again sit still and remain the same. We became alive, possessed – driven to make a difference. And the Torah taught us just how to channel that drive.

Part of above ideas based on thoughts heard from R. Mattis Weinberg.

We “far off” gentiles without hope in this world, but come to love, serve, worship, obey the G-d of Israel, like Ruth, are so grateful that we too can be accepted into the people of Israel and their G-d…because it was HIS eternal plan. Genesis 12:3, Isaiah 56:7.