Exploring the contemporary meaning of the first tragedy that occurred on the 17th of Tammuz, the breaking of the tablets at Mt Sinai.

The fast of the 17th of Tammuz commences a period of mourning of The Three Weeks which concludes with the fast of Tisha B’Av. The Talmud records that the first tragedy that occurred on the 17th of Tammuz was the breaking of the tablets at Mt Sinai.

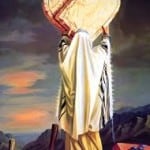

Moses descends Mount Sinai and sees the Jewish people dancing around the golden calf. He takes the two tablets he is holding in his two hands and thrusts them to ground, shattering them. The divine gift of the tablets etched by God now lay strewn on the ground.

Whatever became of the tablets smashed by Moses?

The Talmud answers: The broken tablets were placed in the holy Ark along with the second, intact set ; ‘luchot ve’shivrey luchot munachim be’aron”(Talmud Bava Batra 14b).

The broken tablets were not buried, which is what we generally do with holy items no longer in use. They were placed in the most sacred place, in the Aaron Hakodesh, the holy Ark. Eventually they sat next to the second tablets, the whole set of the Ten Commandments. Together they remained securely protected as the nation journeyed through the wilderness.

Why do the broken pieces remain precious? If they represent the Jewish people disregarding the covenant with God, would we not wish to simply forget about them?

The idea of brokenness appears in a number of significant places in Judaism: We sound the shofar with the broken notes of the shevarim; the Hebrew root word ‘shever’ means ‘broken’. We begin the Seder breaking a whole piece of matzah. When the bride and groom stand under the wedding canopy, a glass is shattered into pieces. These important symbolic rituals represent shattered and broken events in both our personal and communal lives. Breaking the matzah represents the broken life of the slave, the repentant spirit of a remorseful person is symbolized by the broken sounds of the Shofar, and breaking of the glass represents a world that is incomplete without the presence of the holy Temple in Jerusalem.

The two sets of tablets in the Ark offer a striking metaphor. Namely, that brokenness and wholeness coexist side by side, even in Judaism’s holiest spot – in the heart of the holy Ark.

The 16th century Kabbalistic work, Reshit Chochmah, teaches that the Ark is a symbol of the human heart.

People experience brokenness in many ways. One way that many of us experience despair and crushing pain is through the death of a loved one, especially when life is cut short. Those of us who have passed through the ‘valley of death’, those of us who have lost loved ones, know that we forever carry ‘broken tablets’. Loss forever remains a part of us. We carry the aching loss, and for some of us, we carry pain in our hearts and minds forever. The image of the broken tablets, unfortunately, offers an accurate representation of our lives and the life of the world around us. We carry our broken tablets with us always.

After a painful loss, life continues, but now differently than before. We move through life now with two sets of tablets. There are times of joy; there are very happy times. They are encased in the same box; in the same heart. The commentator Rashi says that the two sets of tablets, the broken and the whole sets, sit touching one another. The seat of the emotions is found in the heart. Here, in this one enclosed space, emotions freely move from one place to the next.

The Broken Hearted

The bereaved, and especially those that have suffered painful loss, often live their life with two compartments within one heart – the whole and the broken, side by side. To be a good friend is to know this and to be respectful of the brokenness that always remains.

To be a good friend one needs to accept and be sensitive to this new reality even if this means accepting this painful truth. A friend never asks, “Are you over things yet?” or never says, “It would be best for you to move on.” Instead a sensitive friend says, “What do you need most today?” or says, “I will always be with you.” The most important thing we can do as friends, as family, and as a community is to surround the bereaved with warmth and love, not pity. We need to show that we care – not only in the weeks and months following the loss, but continuously, even years later.

We can help mend fractured hearts when we stay sensitive to those that need our empathy and support. This is how we help bring about ‘shleimut’, wholeness, to a world with so many broken shards.

The Chassidic Rebbe, Reb Menachem Mendel of Kotzk said. “There is nothing more whole than a broken heart.” What does this enigmatic statement mean?

The heart can be patched after one confronts his brokenness and acknowledges his vulnerability. With great strength and resilience those who are broken still find the strength to lead more fulfilling and meaningful lives. Many people have admirably found the faith and willpower from within, and with the support of those around them to accomplish and create great things. They have ennobled their lives and have rebuilt their lives even after suffering the deep pain of loss. This is a testament to the valiant spirit that is endowed in the soul of man. The desire on the part of the bereaved to keep the memory of loved ones alive and to eternalize their spirit in ways both big and small often inspires the bereaved to live with heroic determination and courage.

God cradles the broken tablets side by side with the whole ones in the holiest place in our tradition. The symbol of the broken tablets serves as a poignant reminder of our sacred responsibility to be ever sensitive to those who suffer and to reach out and be understanding and embracing of those who live with ‘broken tablets’ in their hearts.

Moses picks up each precious piece of the tablets, he collects every shard, and he lovingly places every piece in the holy Ark, conveying a message that guides the Jewish heart for all time.